A Modern-Day Jekyll

There is no term to describe the phenomenon of a public figure holding a dark secret for years before being exposed and falling from grace. So I borrowed one from Robert Louis Stevenson.

See accompanying podcast featuring Dr. W. Keith Campbell, Professor of Psychology at the University of Georgia and the author, most recently, of The New Science of Narcissism.

THE INSPIRATION to write Jekyll and Hyde came to Robert Louis Stevenson in a "feverish dream", exacerbated by his chronic tuberculosis and medicinal cocaine use. In the dream, a man transforms into his evil twin.

It was also inspired by a real-life example: William Brody, Stevenson's Scottish compatriot and a famous cabinet-maker, whose furniture Stevenson himself owned.

According to historic-uk.com, "A respected member of Edinburgh society, Brodie was a skillful cabinet-maker and member of the Town Council …However, Brodie had a secret night-time occupation as leader of a gang of burglars... To support his night-time activities Brodie had the perfect day job, part of which involved making and repairing security locks and mechanisms. The temptation obviously proved too much for him when working on the locks of his customer’s houses, as he would copy their door-keys! This would allow him and his three accomplices to return at a later date to steal from them at leisure."

I thought of Stevenson and Jekyll (and Hyde) after weeks of searching for a way to describe a familiar, and luckily rare, phenomenon.

A charismatic public figure -our “hero” - is on a mission. Maybe it's to prove that the measles virus (either live or in the MMR vaccine) causes autism. Maybe it's to perform multiple blood tests on a single drop of blood. Maybe it's to deliver incredibly high returns to investors, or to become the best cyclist in the world.

Then the headlines come, alleging that our hero is a fraud. They usually stem from investigative reporting, whistleblowers, and government investigations. For Madoff, it was the 2008 stock market crash when every investor asked for their money back, a total of $18 billion, only to discover that there wasn't any left.

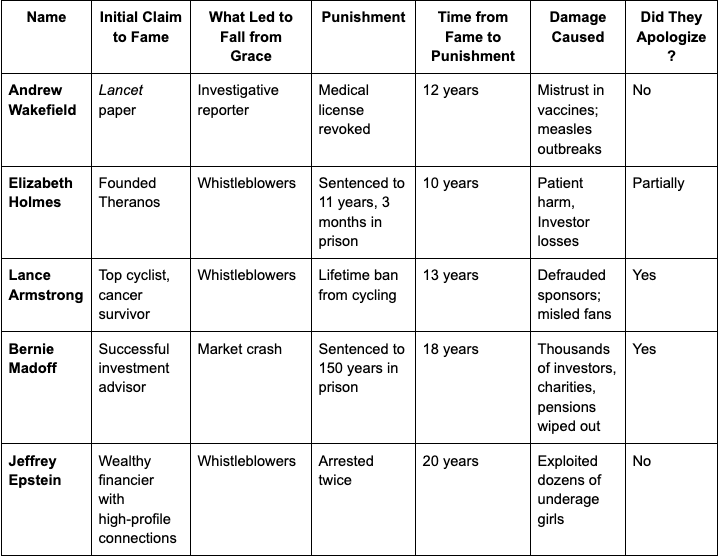

Punishment follows. Jail for Madoff, Epstein, Holmes. Loss of medical license for Wakefield. For Armstrong, ban from all doping-controlled sports, and disqualification of all his Tour De France wins.

Note how many years pass between fame and headlines of fraud - in our five examples, 15 years on average (See table). “I view this situation as one big lie that I repeated a lot of times,” Armstrong eventually confessed.

(In the case of Epstein, there was no mission to fail. Just a desire to commit sex crimes with the rich and famous - but still a need to cover it up).

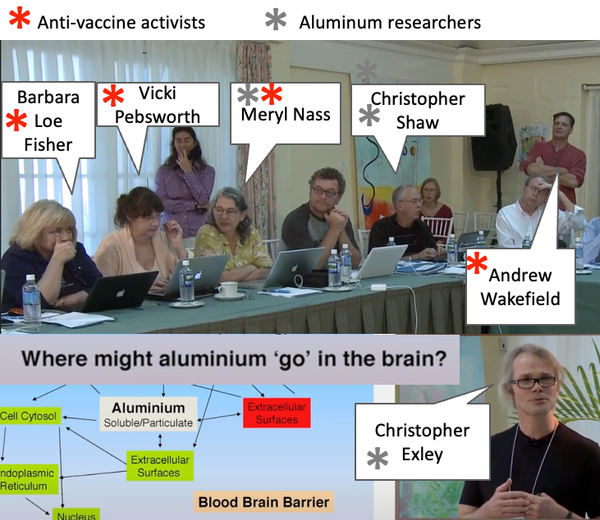

First, how might such prolonged cover-up be accomplished? Perhaps through scientific fraud. After a years-long investigation, Brian Deer reported that Andrew Wakefield made up autism diagnoses for children who did not have them, and forged the timing of their MMR vaccination to fit his theory. In his book that reads like a thriller, "The Doctor Who Fooled The World," Deer describes days of pain and suffering Wakefield subjected autistic children to at his hospital in a vein search for the measles virus, without ethics committee approval. “It shows how self-importance can be self-destructive and harmful to others,” a book review concluded at the time.

Armstrong oversaw a "sophisticated doping network," reminiscent of a criminal enterprise.

Holmes, seeing that her technology was not working out, nonetheless proceeded with a clinical “rollout,” while secretly running patient's blood samples on standard blood test machines. There was a problem, though - not enough blood (Theranos, after all, promised just a drop would be enough). So they diluted the blood drops with water, ran the tests, and then multiplied the results by the dilution factor. But this kind of "dilution-and-multiplication" was not what these standard machines were built and FDA-approved to do. The result: potentially life-and-death errors for patients.

Madoff set up a Ponzi scheme - recruiting vast numbers of new investors and using their investments to pay “interest” to the prior ones.

As fascinating as the “How,” an equally interesting question is “Why.” Are there certain personality features that predispose someone to become a Jekyll?

An online search initially led me to the concept of a “con.”

The term “confidence man,” or “con man” for short, apparently had its first use in 1849 at the trial of one William Thompson, writes Maria Konnikova, a psychologist and expert in deception who became one of the world’s top poker players while doing research for her book, The Biggest Bluff.

“The elegant Thompson …would approach passersby on the streets of Manhattan, start up a conversation, and then come forward with a unique request: ‘Have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until tomorrow,” she writes in her second book, The Confidence Game. Many people did, and obviously never saw their watch again.

Konnikova proposes one predisposing factor for the “con man” behavior: psychopathy.

What is psychopathy? Campbell, the podcast guest, provides a clear definition in his book.

“Psychopathy mixes low agreeableness with low conscientiousness [plus] impulsivity. Imagine someone who is grandiose, cold, callous, and also does whatever he or she wants. Psychopaths are often found in criminal populations because their impulsivity gets them in trouble: they rob, steal, and even kill people.”

Konnikova provides interesting evidence for psychopathy as a characteristic of con artists:

“People who experienced early life lesions in the polar and ventromedial cortex—areas implicated in psychopathy—begin to show behaviors and personality changes that very closely mimic both psychopathy and the grift. Two such patients, for instance, showed a newfound tendency to lie, manipulate, and break the rules. Others described them as ‘lacking empathy, guilt, remorse, and fear, and . . . unconcerned with their behavioral transgressions.’ Psychopathy, then, is a sort of biological predisposition that leads to many of the behaviors we expect from the confidence artist.

Just when I start to wonder whether psychopathy is a characteristic of a Jekyll, Konnikova introduces a new concept - the dark triad.

“But that’s not exactly the whole story. Psychopathy is part of the so-called dark triad of traits. And as it turns out, the other two, narcissism and Machiavellianism, also seem to describe many of the traits we associate with the grifter.”

OK, so we are now adding narcissism - “self-importance, antagonism and sense of entitlement,” and Machiavellianism, being “callous and highly manipulative, believing that the importance of [one’s] aims justifies even immoral means” (quotes from Campbell).

Could this “dark triad” be what the Jekylls have in common, similarly to con artists?

However, one aspect does not fit for a Jekyll: the impulsivity that is characteristic of psychopathy. Says Campbell:

“Narcissism is not typically associated with impulsivity, but [psychopathy] is. In the “real world,” impulsivity might mean stealing somebody’s watch or cheating on a spouse. In extreme cases, people who are antagonistic and highly impulsive often end up in and out of jail. Since they commit impulsive crimes, they get caught, and they don’t often build up enough financial resources to protect themselves from some level of societal justice.

Hard to imagine an impulsive person like that keeping a dark secret for 15 years.

So No to dark triad?

Not so fast, according to Campbell. Some psychopaths can control their impulses.

“Popular novels, movies and television shows, however, often feature psychopaths with high self-control. Hannibal Lecter in the Silence of the Lambs, for example, is a serial killer and cannibal but also a trained forensic psychiatrist who happens to make intricately prepared meals for his victims.

So Yes to dark triad?

But wait again, says Campbell - it may be just plain narcissism!

“In reality, master criminals such as these aren’t common. Jeffrey Epstein seemed like a real-world example of a high-functioning psychopath. Instead, it’s likely that Epstein - and Lector - was as much a narcissist as he was a psychopath.”

“If someone with narcissistic personality disorder had those same antagonistic traits [as a psychopath], they’d exhibit less impulsivity, focus more on looking good, and put more thought into committing crimes. To look good publicly, they would need to avoid getting caught, and they would spend more energy focusing on that or operating in gray areas.”

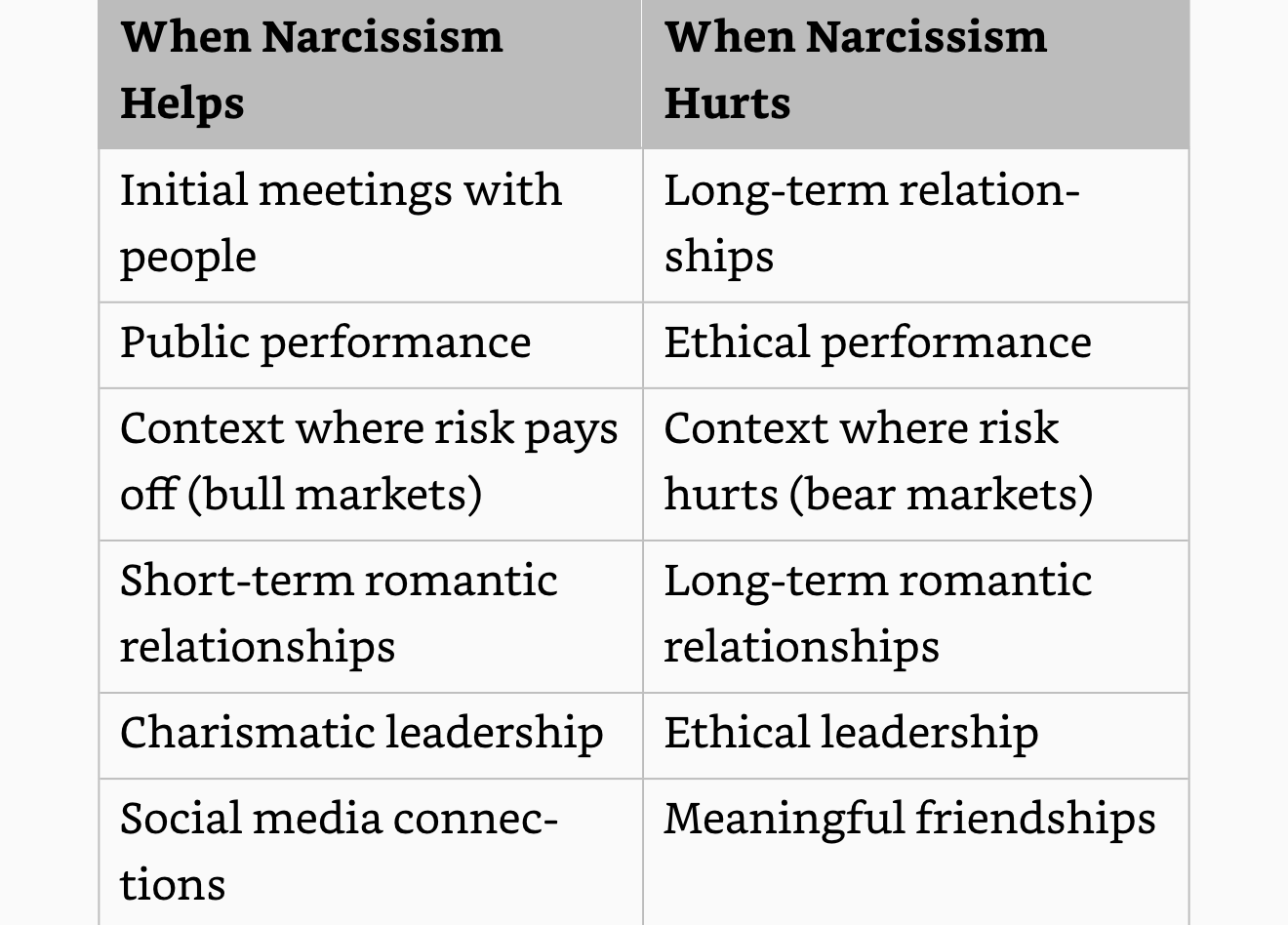

OK, so let’s suppose it’s narcissism that unites all Jekylls. First, Campbell reminds us that narcissism is not necessarily a bad thing. Look at this fascinating table from his book.

Second, is there anything we can do to spot a narcissist?

For a new hire, or a potential romantic partner, the best advice Campbell offers is to consider a person’s past history. “The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior,” he reminds us. “Yes, people change, but it is very rare for a narcissistic person. The motivation is usually not there.”

How about for a public figure?

In the scenarios we discussed, there was no past history, at least not widely known.

“Narcissism can be very difficult to recognize,” says Campbell.