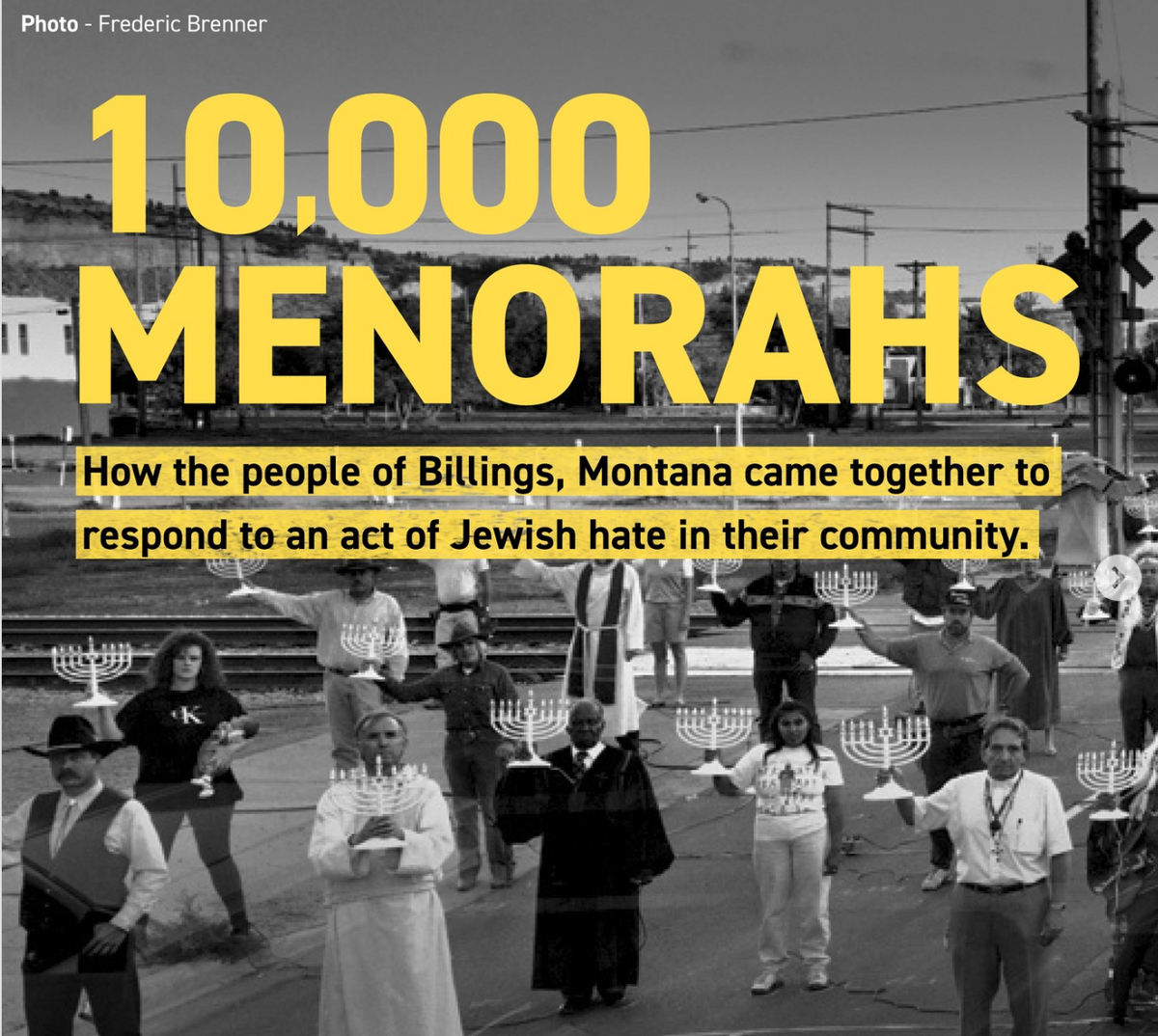

Pirsumei Nissa

I lit the candles - the top one, the shamash, and the first one of the eight, symbolizing the miracle of a little bit of oil lasting for eight days - and was about to put it on the windowsill. "No, not there," my grandmother waived me off. "People will see it."

When my parents and my grandmother emigrated to the US from Russia, they rented an apartment in Brooklyn, NY, on the fourth floor of a brick building facing a two-way street. That December, I came to visit them from Boston to celebrate Hanukkah as a family for the first time in our lives. I brought a Menorah, some candles and a black-and-white brochure with Hanukkah prayers in Russian. The four of us gathered in the kitchen. I lit the candles - the top one, the shamash, and the first one of the eight, symbolizing the miracle of a little bit of oil lasting for eight days - and was about to put it on the windowsill. "No, not there," my grandmother waived me off. "People will see it."

We were not surprised at all. My grandmother survived World War II and waves of antisemitism that followed in Russia by hiding her Jewish identity. Even her co-workers and neighbors did not know she was Jewish. This was common at the time, and easy to do, as religion of all sorts was banned.

On this somber evening as Jews around the world are gathering to light the candles, mourning the loss of innocent victims of Jewish hatred in Sydney, Australia and a school shooting at Brown University, I cannot help but wonder how many of us are thinking the same thought.