From Willowbrook to the Geiers: Families Speak Out

“Once, I went down to the Geiers’ basement to use the bathroom. I saw several ladies packaging drug bottles into boxes. And in the bathroom I saw what appeared to be equipment from a chemistry lab.”

By Alex Morozov and Arthur Caplan

Dr. Caplan is the Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor and founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine’s Department of Population Health in New York City.

Dr Morozov is the CEO and Founder of ETP News.

In the early 2000s, Dr Mark Geier, recently described by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as an “internationally revered physician and scientist,” started collaborating with TAP Pharmaceuticals, the maker of Lupron® - a testosterone blocker, best-known as treatment for prostate cancer and endometriosis. Lupron is also FDA-approved for treatment of precocious (premature) puberty in children.

These were difficult times for TAP Pharmaceuticals. In October 2001, they had agreed to pay the Department of Justice $875 million - the biggest ever fine for healthcare fraud - to settle accusations of kickbacks such as “trips to resorts, medical equipment and money offered to the doctors.'” In addition, Lupron competitors were entering the market.

It’s no surprise that TAP looked for new uses, or “indications” as they are often called, for Lupron. Apparently, they were so desperate that they accepted new ideas from physicians regardless of their qualifications. For example, one private practice doctor in Florida who ran a network of weight loss centers came up with the idea of using Lupron for Alzheimer’s disease, despite having no qualifications in neurology. He “applied for a methods patent… and has entered into an agreement with TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc for a clinical trial involving [Lupron] in Alzheimer disease.”

Geier and his son David followed a similar path. Their invention was to use Lupron for the treatment of autism, based on a discredited theory that autism is caused by mercury in vaccines, and an even more outlandish hypothesis that testosterone binds mercury and prevents its excretion. But Lupron alone would not be enough, the Geiers surmised. They proposed to add Chemet® (also known as DMSA), a pill that helps remove toxic metals from the body through chelation - binding to the metal like a “claw” (from Greek chēlē, meaning "claw"). Chemet is FDA-approved for acute lead poisoning. The Geiers’ idea was that Lupron would free up mercury and Chemet would help remove it from the body.

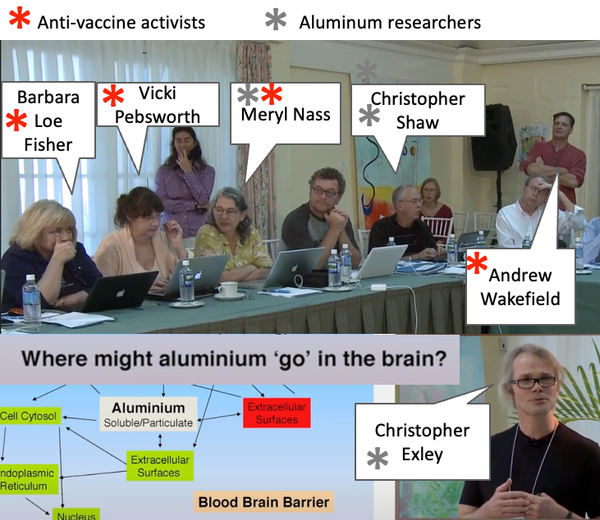

Their project echoed that of Andrew Wakefield, a since-disgraced British researcher who proposed in a 1998 paper that the MMR vaccine causes autism. Wakefield was ultimately stripped of his license to practice medicine in the UK - not just for rewriting his patients' medical histories to fit his theory, or for being secretly guided by an anti-vaxx lawyer, but critically, for performing unauthorized research on autistic children. He subjected them to unnecessary, painful, invasive procedures - colonoscopies, lumbar punctures and others - in a week-long ordeal he personally cajoled the families into. His paper stated that “ethics approval was granted” - but no such approval existed. And when he needed blood from children without autism, he drew it from his son’s friends at a birthday party, aged between 4 and 9, without any authorization, and then joked about it in a conference presentation.

“And you line them up—with informed parental consent, of course. They all get paid £5, which doesn't translate into many dollars I'm afraid. But … they put their arms out and they have the blood taken. All entirely voluntary.”

For the British authorities his abuse of children was the last straw.

As disturbing as Wakefield’s human experiments were, tragically they were not the worst examples involving autistic people.

The Geiers’s experiments were on a much larger scale, involving not just tests, but “treatments.” Their theory was a “witches brew” of other pseudoscientific concepts, including the idea that specifically mercury in vaccines causes autism. This idea was proposed in 2001 by Lyn Redwood and Sallie Bernard, the founders of SafeMinds. The Geiers also drew upon a study by Simon Baron-Cohen, a top autism researcher, that high testosterone levels in utero correlate with autism. Notably, Baron-Cohen never claimed a role for testosterone after birth, and called the Geiers’ idea “horrific.” Additional rationale was a totally bizarre theory that the Geiers themselves later abandoned, that testosterone and mercury form some kind of “sheets in the body.”

One can see why TAP Pharmaceuticals would be excited about autism as a new indication for Lupron. Just as they were reeling from the punishing settlement, the term “autism epidemic” was catching on - coined in April 2000 not by a scientist, but by a US politician, Dan Burton. Grandfather to an autistic child, Burton is well-known for promoting an association between vaccines and autism, inviting Wakefield, Redwood, Bernard and others as witnesses to Congressional hearings. But what is less well-known is Burton’s role in creating the very concept of an “autism epidemic.” He coined the term in an April 2000 Congressional hearing. SafeMinds quickly adopted it, even though scientists cautioned that the “epidemic” was mostly due to a change in diagnostic criteria.

For TAP Pharmaceuticals, however, the reason for the rise would not matter. If Lupron were to be used as treatment for autism, the growing market would create an enormous financial windfall for the company.

In 2004, the Geiers filed a US patent on the use of the Lupron-Chemet combination (or similar compounds) to treat autism.

But they did not stop with the US. Typically, if someone wants to ensure not just US but global rights to an invention, they file an international application as well. This is an expensive proposition. It can cost millions of dollars. So the application was filed with the World Intellectual Property Organization in 2006 not by the Geiers but by TAP Pharmaceuticals themselves, using the company’s law firm.

By that point, the Geiers had already accumulated a cohort of patients recruited at autism conferences, and were working with TAP on designing a clinical trial to test their idiosyncratic theory.

Mark Geier passed away in March 2025. Shortly thereafter, David Geier quietly showed up in the HHS directory as a “Senior Data Analyst.” The Washington Post broke the story: “A vaccine skeptic who has long promoted false claims about the connection between immunizations and autism has been tapped by the federal government to conduct a critical study of possible links between the two, according to current and former federal health officials.”

Ignoring the furor that followed, Kennedy confirmed in a Cabinet meeting on April 10 that such a study was being planned, and quickly. “By September, we will know what has caused the autism epidemic, and we’ll be able to eliminate those exposures.”

The public outcry and congressional questions continued. Finally, in a lengthy June 7 post on X, Kennedy defended David Geier, saying that he was brought in “to advise other scientists” based on his “unique expertise” and “extensive background as a research scientist.”

The Lupron clinical trial the Geiers conducted paints a very different picture: a father-and-son team that, in search of personal enrichment, performed unauthorized experiments on autistic children for years in violation of multiple ethical safeguards, reminiscent of human research horrors of the past - horrors that led to these safeguards being created in the first place.

This is the story of children subjected to dangerous experiments - an autistic girl Nina, and an autistic boy Jalen, based on conversations with their families. David Geier refused to be interviewed, as did several TAP Pharmaceutical executives.

(It appears that Geier's work at the HHS was delayed due to difficulties accessing the data from VSD, Vaccine Safety Datalink. Therefore the focus of Trump's September 22 "Autism press conference" was on Tylenol, based purely on published studies. Geier's work, in contrast, is focusing on aluminum, we predicted. Trump did say,"we want no aluminum in the vaccine," in his remarks.)

The first problem the Geiers faced was that as inventors of the treatment being studied, they would benefit directly from the success of the clinical trial. Could they also be unbiased “investigators” - actually running the trial, deciding which patients are appropriate, managing toxicity of this new, never-before-tested drug combination, analyzing the data and publishing the results?

This arrangement would be categorized by current US regulations as a “Significant Conflict of Interest.” While not technically forbidden, it requires a special conflict management plan, informing patients of the conflict so they go into it with eyes wide open; setting up independent monitoring of the trial by a separate Conflict of Interest (COI) Committee, and restrictions on decision-making by the conflicted investigator.

Why not pass on the trial to other, less conflicted doctors to run?

Here the Geiers had another problem. They had big plans that were independent of TAP Pharmaceuticals. They called their newly invented treatment “Lupron Protocol” (not to be confused with the clinical trial protocol - more on that later) and planned to license it to other doctors for a fee, in a “franchise” model similar to how for example Pizza Hut or McDonalds do not operate each location themselves but sell a license to independent owners.

Let’s stop for a second and reflect on this. Here is a doctor and his son who are developing a new treatment for autism. But they are doing it not to share their knowledge with other doctors, via a publication or presentations at conferences, as would be usually done. Instead, they want to (and in fact, they did) sell this knowledge to other doctors for a fee.

First, this is unprecedented. There are some examples of surgeons patenting techniques and selling to their colleagues. But we know of no other example of what the Geiers did: taking medical treatment that is FDA-approved for one purpose, packaging it into a “protocol” for another purpose, without FDA approval, and charging doctors for the privilege of using it.

Second, clearly this represents another conflict of interest - potentially even more significant than the TAP collaboration and patent.

And third, this explains why the Geiers wanted to conduct this trial themselves, as the people who would then be licensing (franchising) their “protocol” to other doctors. They had to be in control.

For all these reasons, the normal process of starting a clinical trial would not work for the Geiers.

This normal process would require approval of an Institutional Review Board (IRB). This is ordinarily very easy. There are about 2300 IRBs in the US. Most serve individual academic institutions, but some operate independently and will review any clinical trial for a small fee. All are required to be registered by the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) within HHS, and must adhere to a whole set of requirements as mandated by the US Code of Federal Regulations.

It is safe to say that no IRB would approve a clinical trial in which the two lead investigators own a patent on the treatment being studied, and far worse, have plans to license it to other physicians for a fee.

So the Geiers came up with an ingenious solution: they created their own IRB with themselves as members.

But before we get to that, why do these IRBs exist, and since when? Many of us take the existence of these safeguards for granted. It makes sense - before some doctor performs an experiment on people, they need to persuade an independent committee that it’s ethical.

Shockingly, the IRB approval requirement has not been in place that long. And it was partly the tragedy of another autistic child and others that ultimately led to these regulations being put in place.

***

Nina Galen was diagnosed with autism when she was less than 2 years old, her mother, Diana McCourt, told me on a recent afternoon in her Upper West Side apartment. On the bookshelves behind her were books by her husband, Malachy McCourt, and brother, Frank McCourt.

“We took Nina to see a psychiatrist on Horatio Street, here in New York City. She could not walk, so I carried her in my arms,” McCourt told me. Her face is devoid of emotion, but looking in her eyes, I see endless sorrow. “She has autism,” the psychiatrist said. “It’s hopeless.”

By the time Nina turned 8, McCourt was becoming desperate. “Nina suffered from severe anxiety that caused her to hurt herself,” she recalls. As a result, Nina had to be supervised 24 hours a day.

“I had two other children of my own, and my second husband, Malachy, had two of his. It became impossible for us to take care of Nina.” Out of desperation, McCourt left Nina in the hands of researchers.

The Geiers would ultimately see hundreds of similarly desperate families and offer hope of “cure” for their children with their Lupron+Chemet “protocol.”

But Nina was not one of them. The year was 1971.

“I tried placing Nina in a day center. But I could not find one that was equipped to handle someone with her level of disability.”

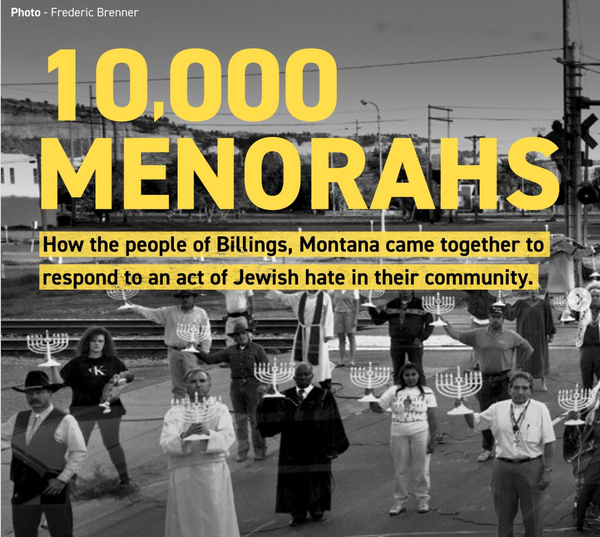

Finally, McCourt was left with only one option: placing Nina into an institution. There were several in the New York area. One, Letchworth Village, was “so awful that the McCourts steered clear of it.” They chose one whose name still evokes dread and horror to this day: Willowbrook.

According to a recent expose by ACLU called “Cleaning Up the Snake Pit,”

The Willowbrook State School, New York City’s institution for people with developmental disabilities, bore a superficial resemblance to a college campus. Opened in October 1947 by the New York State Department of Mental Hygiene, Willowbrook consisted of many buildings, most of them brick, surrounded by grassy areas and spread out on a tract of about 300 acres on Staten Island. An exterior view of Willowbrook made it seem a pleasant place… in 1972, it had about 6,000 “inmates,” even though the hospital was built to house a maximum of approximately 4,000 residents... In 1965, Robert F. Kennedy, then a U.S. senator from New York, had paid an unannounced visit to the institution and denounced its conditions… After visiting Willowbrook, Kennedy described the facility as a “situation that borders on a snake pit.”

But Willowbrook residents would have to wait for another 6 years - to be brought to light one more time - before any changes would come.

In 1972… local ABC television journalist Geraldo Rivera had managed to get a camera into the institution for a few minutes and had broadcast some disturbing images of children wallowing in their own feces and urine. Not content with simply showing viewers the conditions, Rivera described the stench of the facility. “It smelled of filth. It smelled of disease, and it smelled of death,” he reported.

Incidentally, Nina was not the only autistic child at Willowbrook. Allison Singer, the President of the Autism Science Foundation, recalls that “When she was a little girl, in the 1970s, she would visit her older brother, who has non-verbal autism with a cognitive disability, at the now-infamous Willowbrook State School on Staten Island. ‘I just remember hearing a lot of screaming and moaning.’ I hated it.”

Michael Wilkins, the famous Willowbrook physician and whistleblower who invited Geraldo Rivera for an unannounced visit, concurs. “I did not know what autism was when I was working at Willowbrook. I did not learn about it in medical school. But now, as I lay at night and remember the Willowbrook children, I know many of them had autism. We had a whole floor of higher-functioning children - many of them likely were autistic,” he told us.

Horrific living conditions were only one of the dangers. “Disease and neglect were everywhere, and multiple residents died from untreated illness and abuse,” Forbes recently noted.

One disease that was rampant at Willowbrook was hepatitis. In the early 1950s, this attracted the attention of Dr Saul Krugman, a hepatitis researcher at NYU. This was not vaccine research, yet. The hepatitis vaccine would be developed 20 years later by others. There were some basic questions to answer first.

At the time, it was known that hepatitis spreads from person to person and has caused many epidemics. Some of them were clearly spread by what is called the “fecal-oral route” - an infectious agent in the stool of one person somehow ends up in the mouth of another, such as through poor handwashing. Other hepatitis epidemics were caused by contaminated needles, thus were blood-borne. It was also known that hepatitis was caused by a virus.

But a key question remained unanswered: were these different types of epidemics caused by the same virus, or different ones?

To Krugman, Willowbrook offered a unique opportunity to answer this question.

Krugman’s first human experiment was to demonstrate that a blood preparation containing antibodies, called gamma globulin, could protect Willowbrook residents from hepatitis. It was a crude randomized trial - in each building, inmates were divided into two groups: one group was given gamma globulin, one was not. There was no indication in the publication that informed consent was obtained. One risk, well-known already at the time, was of contracting a blood-borne disease from gamma globulin itself, prepared from pooled blood of multiple donors. Some steps were taken when preparing the globulin to kill infectious agents, but it was unknown whether these steps were fully effective. (Today we know that Hepatitis B or C virus would not be killed by these steps.)

The trial was remarkably effective, reducing the rate of hepatitis infection 10-fold.

What next? The ethical thing would have been to administer gamma globulin immediately to the control subjects who had not received it yet, and to begin administering it regularly to stamp out rampant infection (prior studies showed that the effect lasts for many months). But Krugman had other plans. He wanted to understand “the mechanism of this protection.” What happens when someone is infected with hepatitis after receiving gamma globulin? Hence his idea was born of “feeding virus to patients.”

This required controlled infection in a separate ward. Regular wards with “children wallowing in their own feces and urine,” as observed by Geraldo Rivera, would not do. And participants needed to be new arrivals, not yet exposed to hepatitis. How to explain to the parents why their children were to be housed in a separate wing, observed by doctors and nurses? And how to convince them to subject their children to purposeful infection with hepatitis?

Kuperman found a carrot to entice the parents with: skipping the waiting list. According to Forbes,

When Dr. Krugman and Dr. Giles began the Willowbrook hepatitis experiments, they used the conditions of Willowbrook to their advantage for recruiting new families. Despite its well-documented horrors, Willowbrook was still one of the only options for children with severe disabilities, and there was a long waitlist. Dr. Krugman offered several parents, including Nina Galen’s, the ability to jump the line and have their children put in the newer, cleaner research wards with more staff—if they joined the experiments. “I did feel coerced,” McCourt says, “I felt like I was denied help unless I took this [opportunity].”

Krugman also told parents that since hepatitis was already prevalent at Willowbrook, their children may as well have the chance for a vaccine. McCourt remembers being told her daughter could get an “antidote” to hepatitis if she joined the experiment. When she asked why the hepatitis studies couldn’t be done on primates, she was told that using animals would be “too expensive.”

“Permission was obtained from the parents of children five to ten years of age newly admitted to Willowbrook,” wrote Krugman and colleagues in their 1958 New England Journal of Medicine article. “They were brought directly to an isolation unit and had no contact with the rest of the institution. They were cared for by physicians, nurses and attendants who also had a minimum of traffic with other patients and personnel.”

Then came the infection. From 1955 to the 1970s, Krugman and colleagues performed a series of experiments, injecting children with hepatitis-infected blood or forcing them “to drink chocolate milk mixed with feces from other infected children in order to study their immunity.”

In March, 1965, Dr Henry Beecher, a professor of anesthesiology at Harvard Medical School, arrived at the Brook Lodge, near Kalamazoo, Michigan, the former home of William E. Upjohn, the founder of the pharmaceutical company bearing his name. Beecher was there to present at the Upjohn-sponsored conference “intended to be an opportunity for scientists to explain the process and challenges of drug development to science journalists while fostering congenial relations between the press and the pharmaceutical industry. Speakers were well-known academics from across the country, and topics ranged from experimental design to the placebo effect to safety issues. Attendees represented all wire services, major daily newspapers including the Los Angeles Times and New York Post, as well as periodicals such as Time and Newsweek.”

Upjohn invited Beecher to speak on the ethics of human experimentation. In the weeks leading up to the conference, Beecher alerted the organizers that his talk would be a “bombshell,” and asked to extend his time to 40 minutes - they agreed.

In a session called “Special Problems in Clinical Research,” Beecher dropped his payload on the topic of the “The abrogation of ethical responsibility among American researchers.” “He described cases in which researchers withheld penicillin from soldiers with rheumatic fever, conducted unindicated thymectomies to study its immunologic effect, transplanted a melanoma tumor from one patient to another…”

Among his examples was Krugman’s Willowbrook research.

The aftermath was swift: as media outlets fanned out to broadcast Beecher’s scathing accusations, researchers pushed back, accusing him of “gross and irresponsible exaggeration.” Beecher persisted, writing an article based on his talk. The Journal of the American Medical Association refused to publish it. The New England Journal of Medicine ultimately did, after its Editor-in-Chief overruled six of seven peer reviewers.

Beecher’s 1966 NEJM publication prompted the US Surgeon General to request an investigation. But no substantive change ensued.

When Nina Galen entered Willowbrook in 1971, five years after Beecher’s NEJM paper, Krugman’s experiments were still ongoing, and she became yet another victim.

“I never found out what they did to her,” McCourt told me. “I came to visit her every week. First, they placed her in an isolation room by herself, sedated with medication. Later, they moved her to a general ward. When they brought her out to see me, she always wore different clothes, as though she was hastily dressed in whatever was nearby. She looked pale, and sometimes had bruises on her body.”

Real change had to wait for another shocking human experiment to be revealed. Peter Buxtun, a 1971 law school graduate, could no longer hold a dark secret he had learned as a public health employee in 1960s, and which the CDC ignored when he alerted them in 1966. On July 25, 1972, The Associated Press broke the story of Tuskegee, based on the documents Buxtun provided.

“Of about 600 Alabama black men who originally took part in the study, 200 or so were allowed to suffer the disease and its side effects without treatment, even after penicillin was discovered as a cure for syphilis,” AP reported.

This was the final straw. In 1974, Congress passed the National Research Act, Public Law 93-348, which became the first federal law mandating IRBs.

Jalen Coates was born in 2000 to a Jewish mother, Kim, and an African-American father, Cori. Diagnosed with severe autism as a young boy, Jalen never learned to talk, and had frequent temper tantrums that became harder to manage as he became stronger. One day, when he was 8 years old, his therapist told Kim and Cori about a doctor nearby in Maryland who was offering a chance of cure - Mark Geier.

“Dr Geier’s office was beautiful. Him and his son were very nice to us,” recalled Kim and Cori in a recent zoom call. “Jalen had a temper tantrum right in their office. We were scared he would break their furniture. But the Geiers were so patient. ‘Just wait, he will quiet down,’ they said.”

The Coates do not remember signing any informed consent document. In fact, they were not aware they were participating in a clinical trial at all. “If I knew this was a clinical trial, I would have never done it,” Kim said.

But even if they were provided with the informed consent form, the one prepared by the Geiers was grossly inadequate. A short two pages, it failed to explain what the study was about, and failed to mention important side effects or the glaring conflicts of interest.

The clinical trial protocol the Geiers followed was even shorter - only page, containing none of the required elements that the IRB would typically look for to determine whether the clinical trial is acceptable: What are the objectives of the study? What is the rationale? What is the exact patient population - do certain patients have contraindications? How to manage toxicity?

To obtain insurance reimbursement for the cost of Lupron, the Geiers entered their patients’ diagnosis not as autism, but as precocious puberty - an FDA-approved indication. “Lupron was covered by our insurance,” Kim recalled.

With Chemet, it was more complicated - the drug is only FDA-approved for acute lead toxicity, so insurance would not cover long-term use. “We could not afford Chemet, so Jalen only received Lupron.”

This, in the language of clinical research, is called a “major protocol deviation.” The protocol calls for two treatments - Lupron to block testosterone, and Chemet to remove mercury (however ridiculous the rationale). By skipping one of the components, the Geiers managed to deviate even from their 1-page protocol - and for an absolutely egregious reason - the family’s inability to pay.

Lupron did help with temper tantrums - an expected consequence of lowering testosterone. But Jalen was “crying all the time,” Kim said, “and we did not know why.” He gained weight and developed gynecomastia - breast enlargement. All are common Lupron side effects.

Investigational drug product is obviously a key element of any clinical trial. Jalen was on Lupron for 3 years. The first two, the Coates obtained Lupron from a pharmacy. Except it was not Lupron, but a generic version, leuprolide, made by Teva pharmaceuticals, Kim recalled.

“Then, for the last year, the Geiers told us to pick it up from their house,” Kim recalls. “It came in glass bottles with a home-made label that barely stayed on the bottle,” she said. “Once, I went down to the Geiers’ basement to use the bathroom,” she recalled. “I saw several ladies packaging drug bottles into boxes. And in the bathroom I saw what appeared to be equipment from a chemistry lab.”

What was the chemical Jalen was receiving - was it even leuprolide? Did the Geiers make it in their basement? Or was it just water? We don’t know.

“Did Jalen’s side effects get better,” I asked Kim. She said they did not, so presumably there was some version of leuprolide that Jalen was getting in the self-made bottles.

Here was the third mechanism by which the Geiers profited from prescribing Lupron (or some version of it) to their clinical trial subjects: in addition to the patent and the licensing fees paid by other doctors, they also ran a pharmacy and charged insurance companies for the Lupron their patients received.

After three years, the Geiers stopped their treatment to allow Jalen to enter puberty. Not surprisingly, he was not cured of his autism. His temper tantrums came back.

The Coates stopped seeing the Geiers, unaware that Jalen may yet suffer long-term consequences of Lupron use. Some patients develop osteoporosis or dental issues.

“The idea of using GnRH agonists to treat autism, especially based on such a questionable theory, is deeply troubling,“ Dr Lars Dinkelbach, a Clinician Scientist at the Department for Pediatric Endocrinology at the University of Essen in Germany and an expert in puberty and its medical modification, told us. “Pubertal timing plays an important role in neurodevelopment. That makes me think we need to be especially cautious when considering interventions like GnRH agonists, particularly in vulnerable populations. The long-term consequences of such treatments, including potential effects on fertility, bone health, and mental health, are still not fully understood.”

The Geiers ultimately published their clinical trial in two scientific papers, both with David Geier as first author. The first article, called “A clinical trial of combined anti-androgen and anti-heavy metal therapy in autistic disorders,” was published in 2006 and reported data for 11 of the trial participants.

Adverse events - a critical aspect of any clinical trial - are not mentioned at all in the “results” section of the paper. The discussion section states, “It was observed that the treatment protocol employed in the present study resulted in minimal significant adverse health effects… The patients’ parents also reported no significant adverse health effects of the treatment protocol employed.”

We don’t know whether Jalen was one of these 11 patients, but he alone had three adverse events - crying, obesity and gynecomastia. And the contemporaneous online chatrooms are full of patients’ stories of side effects from the Geiers’ Lupron+Chemet treatments: increased behavioral problems, “brain fog,” urinary incontinence, yeast infections, and others.

The other publication of this clinical trial’s results came in the form of a paragraph in another article by the Geiers, again with David as the first author. “In our own clinical experience we have observed that leuprolide acetate (LUPRON®) administration to nearly 200 patients diagnosed with ASDs significantly lowered androgen levels and has resulted in very significant overall clinical improvements in socialization, sensory/cognitive awareness, and health/physical/behavior skills, with few non-responders and minimal adverse clinical effects to the therapy.”

Neither paper has been retracted. Since their publication, case reports have appeared in the literature of autistic children treated with Lupron around the world. It’s not a surprise - to a physician coming across these papers, the treatment looks promising - tremendous efficacy and (if one trusts the authors) “minimal adverse effects.”

The Geiers treated over 300 autistic children, and some adults, with their “Lupron Protocol.” They were ultimately stopped thanks to Kathleen Seidel, the mother of an autistic child and the creator of Neurodiversity Weblog (now archived as Neurodiversity.net). In 2006, Seidel noticed the reference to an IRB in one of Geiers’ publications. Through a Freedom of Information Act request, she obtained the membership of this IRB. What she received was concerning.

“Whereas the IRB was registered in March 2006, the research described in the article was conducted between November 2004 and November 2005. Further, according to The Common Rule, Mark Geier [IRB chair] and David Geier would be ineligible to vote on any of their own research proposals. Anne Geier would be ineligible to vote on any research proposed or conducted by her husband or son. Rev. Lisa Sykes would be ineligible to vote on any study in which her son is a participant. As a co-investigator with Mark and David Geier in their Lupron research, John Young, too, would be ineligible to vote on any IRB supervising that research. Of the seven members of the IRB, only a minority of two — Kelly Kerns and Clifford Shoemaker — would be eligible to vote on the research described in the article — and only if they are free of any personal or financial interest in its outcome.”

Mr Shoemaker is a vaccine injury lawyer, and Mrs. Kerns is an anti-thimerosal activist, Seidel noted.

A reader of Seidel’s blog conveyed these findings to the Maryland Medical Board, which conducted a multi-year investigation and ultimately concluded:

Dr. Geier has displayed in this case an almost total disregard of basic medical and ethical standards by… providing “informed consent” forms that were misleading and in at least one case blatantly false. He provided treatments supposedly according to an investigational protocol, but the investigation was approved only by a sham IRB, and he applied protocols to patients who did not fit his own profile ... At the same time, he profited greatly from the minimal efforts he made for these patients. In plain words, Dr. Geier exploited these patients under the guise of providing competent medical treatment…”

Mark Geier’s license to practice medicine was permanently revoked in 2012; he petitioned for judicial review but the revocation was upheld.

The saga of unethical conduct does not end there. To circumvent the loss of his license, Mark Geier asked at least one colleague, and possibly others, to prescribe Lupron to his patients on his behalf. He then moved his operation to his franchises other states, and continued until each of the states, one by one, stripped him of those licenses as well.

Mark Geier was the only research mentor his son ever had. This alone would be concerning. But worse, David Geier worked side-by-side with his father in the clinic, sometimes even seeing patients by himself, ordering and interpreting tests, and even forging his father’s signature on at least one test order. He was sanctioned and fined for practicing medicine without a license. His petitions to overturn this ruling, like his fathers had, failed.

Were all the hundreds of patients who ultimately received the “Lupron Protocol” participating in the original clinical trial? Or was the trial completed at some point, and slowly morphed into clinical practice, without a full publication and accounting of results? I asked Seidel this question. “I do not recall ever seeing any indication that some patients were included in the Geiers' "clinical trial" and some were not. Honestly, although they sometime used the term "clinical trial," I suspect that the Geiers had little conception of what is involved in a true clinical trial; rather, they used the term "clinical trial" to put a scientific gloss on what was in fact uncontrolled pharmaceutical experimentation on autistic children conducted without ethical review,” she said.

Jalen is now 25. I got to meet him recently - a handsome young man, he shook my hand when I was leaving. He remains non-verbal and is now on 4 medications to control his temper tantrums, with some success.

Nina lives in a group home with two similarly disabled roommates and 24-hour care, paid for by Medicaid. Dr. Bernard Carabello, a long-time resident of Willowbrook who became a disability advocate in New York State, told us he is worried about Nina and others like her. “Medicaid cuts will have a devastating effect on the services they and scores of other disabled people are receiving,” he said.

And David Geier? He is now at the HHS, in charge of Kennedy’s “autism study.”